PRU Provision – Professional opinion

This report provides critical evaluation of the arguments for and against the proposed creation of new Pupil Referral Units (PRU) for pupils spanning Key Stage 3 and 4.

PRUs are integral to the Behaviour Support Plans (BSPs) of most Local Education Authorities (LEAs) in England and Wales. Section 527A of the 1996 Education Act placed a duty on all LEAs to produce a BSP which sets out local arrangements for children who are regarded as having ‘behavioural difficulties’. Each LEA was required to publish its BSP by 31 December, 1998. At the same time, however, the core function of BSPs was to be their role in promoting inclusion. Thus, Circular 1/98 identified educational inclusion as one of its policy aims, stating that:

Many pupils with behavioural difficulties are educated within a mainstream setting with schools accessing support services as appropriate. The developing inclusive approach towards education for pupils with special educational needs, including those with behavioural difficulties, should result in this being the case for a greater proportion of such pupils where schools believe they are able to cope effectively with them (DfES, 1998a)

In most LEAs full time education is offered to all excluded and disaffected pupils of secondary age: permanent places at the PRU are often offered for pupils excluded or disaffected from school at KS4

Arguments in favour of PRUs

The ‘son of the sanctuary’ arrived with the publication of the government circulars collectively entitled ‘Pupils with Problems’ (DfES, 1994a – 1994e). These included Circular 11/94, which was largely devoted to the education of young people in pupil referral units (PRUs). The Circular recognised that units which had previously dealt with young people who had been excluded from school ‘have until now had a dubious legal status’. Moreover, it confirmed the haphazard manner of referral adopted by many existing off-site units, stating that the ‘How and why pupils are referred to units currently varies between LEAs and between units and rarely seems to be determined by clear and consistent LEA policy’ (para. 28). Accordingly, the Circular sought to promote the establishment of ‘a new type of school (sic), to be known as a pupil referral unit’ (para. 25). The Circular also indicated that existing off-site units will be henceforth termed PRUs. There are clear benefits to the LEA and others of creating the proposed PRU as follows:

- Full time education possible for larger number of pupils than previously possible

- Excluded pupils have educational provision to attend

- Administratively simpler to have one large unit to place pupils in

- Transition between KS3 and KS4 made easier by pupils sharing site

- Pupils are offered opportunities that they can miss while in a mainstream context, such as social skills training; personal target setting; team-building challenges; and sports activities.

- When pupils are older, the PRUs provide joint PRU/college courses, attendance at skills centres for vocational training and work experience.

- Provision of short term respite for all involved leading to reintegration of pupils to mainstream a ‘revolving door’

Arguments against PRUs

It will be immediately obvious at the outset that provision of alternative formats of education in a segregated setting, as in the case of pupil referral units (PRUs), raises a policy paradox. To what extent is such provision commensurate with the spirit and letter of the Government’s Programme of Action, which emphasised inclusion for all?

- Segregation of pupils in unit provision damages self esteem and decreases likelihood of successful transition back into mainstream school and community life.

- Creates a university for crime, swearing and violence. Most learning for students of all ages is social and by imitation.

- Little evidence to suggest that such provision increases achievement for pupils

- Little evidence that such provision actually improves behaviour. In fact high likelihood of more learned negative anti social behaviour

- Longer term negative outcomes for pupils placed in such provision likely to include prison, mental health problems, suicide, drug addiction and relationship problems

- Large majority (likely to be over 90%) of PRU pupils will be male. This does not offer much equity of opportunity for girls with emotional needs and raises a number of significant issues for a virtually all boy provision. Overrepresentation of black pupils in PRU provision following exclusion feeds the racism already present within society reflected in exclusion figures shown in the Appendix below for one LEA.

- Absence of healthy male peer role models. Who are these pupils to learn from? Most learning is social. Pupils learn from one another.

- Building on a ‘broken model of provision’ From as early as the 1970s and the early part of the1980s, there was the operation of a large number of segregated units which, according to both contemporary and more recent analysis, were largely inadequate and inequitable (Basini, 1981: Drew, 1990). Characteristically the ‘off-site unit’ for disruptive pupils comprised often poorly maintained accommodation (Dempster, 1989), largely informal modes of referral (Bash, Coulby and Jones, 1985), restricted and poorly resourced curricular opportunities (Garner, 1987), and frequently inexperienced, if well-meaning, teachers (DES, 1989). Will new PRUs really be any better?

- Circular 11/94 blandly asserts that the aim of PRUs should be ‘to secure an early return to mainstream’ (p.3). Evidence so far suggests that such good intentions are seldom brought to fruition, as pupil and teacher accounts from PRUs illustrates.

- Most of the students in a study of PRUs by Garner (2000) indicated a desire in pupils to remain in the PRU until they had reached compulsory school leaving age (16 years in England and Wales). This way of thinking could be explained in terms of the ‘push and pull’ theory. The students, in spite of expressed reservations about the quality of the accommodation provided for their PRU, felt a sense of belonging. Not only was the PRU acting in a positive manner in retaining its students in a ‘segregated’ setting (the ‘pull’), but the local mainstream schools presented an ethos and orientation which the students felt were not conducive to their successful re-integration (the ‘push’).

- Cynical attitudes to reintegration among teaching staff ‘I’m sick of both us and our students being used as political footballs. It is about time somebody had the guts to state what most people working in PRUs have known for years – these kids won’t survive in the mainstream, and teachers there don’t want them to’ (Garner, 2000).

In conclusion

Whilst seeming an attractive option to Governments, schools and LEAs there is no history or evidence to support PRU’s efficacy with regards to behaviour change, reintegration or inclusion within a mainstream school and community. The risks of greater alienation, racism, lowered self esteem, the learning of new negative anti social behaviour very likely to lead ultimately to mental health, relationship and criminal behaviour problems should be enough to deter the further development of this model of working.

Whilst we await evaluation studies of the emerging ‘on-site’ exclusion units, there is already data which suggests that there remain important question marks regarding the effectiveness of PRUs. Furthermore, those who are currently engaged as the main ‘actors’ in these settings (notably the pupils and the teachers) provide evidence of both resource-failure and policy paradox. In attending to them I suggest that PRUs (and, by inference, on-site exclusion units) run contrary to the spirit of inclusion. They remain, in spite of some improvement – a replica of earlier, unsatisfactory segregated provision and stand as confirmation that, in these cases of many EBD children, inclusive thinking has yet to become embedded within practice. (Professor, Philip Garner 2000 – Nottingham Trent University, UK)

There are many other fresh approaches to managing behaviour within an inclusive ethos which should be given priority for resources and development energies in all Leas across the UK. A number of these can be seen referred to on our web site inclusive-solutions.com.

References

BASH, L., COULBY, D. and JONES, C. (1985) Urban Schooling: theory and practice. Eastbourne: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

BASINI, A. (1981) ‘Urban schools and “disruptive” pupils’, Educational Review, 33 (3), 37-49.

BUSH, L. and HILL, T. (1993) ‘The right to teach, the right to learn’. British Journal of Special Education, 20 (1), 4-7

COOPER, P. (1999) ‘Educating children with emotional and behavioural difficulties: the evolution of current thinking and provision’, in P. Cooper (ed.) Understanding and Supporting Children with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

COULBY, D. (1984) The creation of the disruptive pupil’, in Lloyd-Smith, M. (ed.) Disrupted Schooling. London: John Murray, 98-119.

DEMPSTER, L (1989) ‘Dangerous units remain open’, The Times Educational Supplement, 3 February.

DEPARTMENT for EDUCATION (1994a) Pupil Behaviour and Discipline. Circular 8/94. London: DfE.

DEPARTMENT for EDUCATION (1994b) The Education of Children with Emotional and Behavioural Difficulties. Circular 9/94. London: DfE

DEPARTMENT for EDUCATION (1994c) Exclusions from School. Circular 10/94. London: DfE.

DEPARTMENT for EDUCATION (1994d) The Education by LEAs of Children Otherwise than at School. Circular 11/94. London: DfE.

DEPARTMENT for EDUCATION (1994e) The Education of Children being looked after by Local Authorities Circular 13/94. London: DfE.

DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION and EMPLOYMENT (1997) Excellence for All Children. Meeting Special Educational Needs. London: DfEE.

DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION and EMPLOYMENT (1998a) Guidance on LEA Behaviour Support Plans. (Circular 1/98) London: DfEE.

DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION and EMPLOYMENT (1998b) Meeting Special Educational Needs. A Programme of Action London: DfEE.

DEPARTMENT FOR EDUCATION and EMPLOYMENT (2000) London: DfEE.

DREW, D. (1990) ‘From tutorial unit to schools’ support service’. Support for Learning, 5 (1),13-21.

GARNER, P. (1987) ‘Disruptive Pupils: a study of two approaches in a London Borough’. Unpublished MA Thesis. University of London: Institute of Education..

Philip Garner (2000)- Nottingham Trent University Paper Presented at ISEC 2000

Pupil Referral Units: A Policy and Practice Paradox

GARNER, P. (1996) ‘A la recherche du temps PRU: case study evidence from off-site and pupil referral units’. Children and Society , 10 (3), 187-196.

GARNER, P. (1999) Pupils with Problems. Rational fears…radical solutions. Stoke-on-Trent. Trentham Books.

OFFICE FOR STANDARDS IN EDUCATION (1993) Achieving Good Behaviour in Schools. London: HMSO.

TOMLINSON, S. (1982) A Sociology of Special Education. London: Routledge.

Colin Newton and Derek Wilson

Inclusive Solutions

20th December 2002

Appendix: Key Excerpts relevant to PRUs taken from one LEA’s Behaviour Support Plan 2001

Statistics on Exclusions in Hammersmith and Fulham

3.3 Exclusions Data

3.3.1 The following tables show firstly how Hammersmith and Fulham compare statistically, both locally and nationally, in terms of exclusions from information provided by the DfEE, and where this is not possible, the information relating specifically to Hammersmith and Fulham.

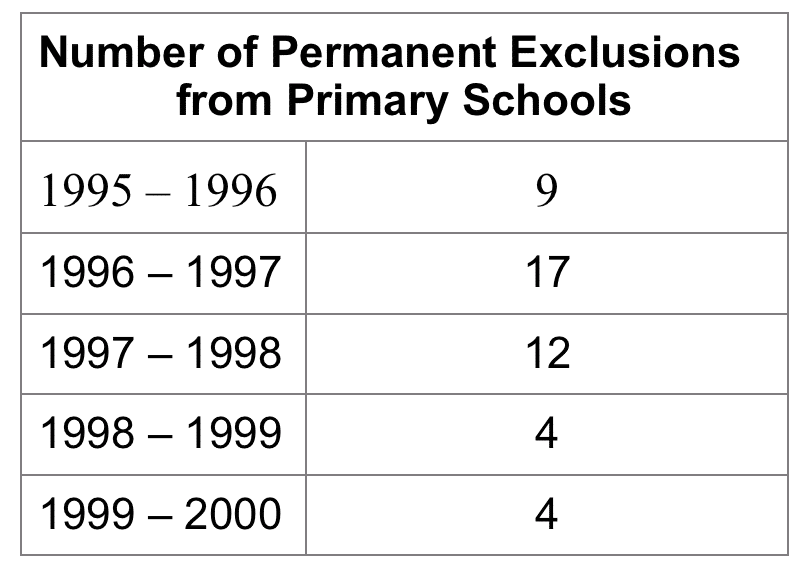

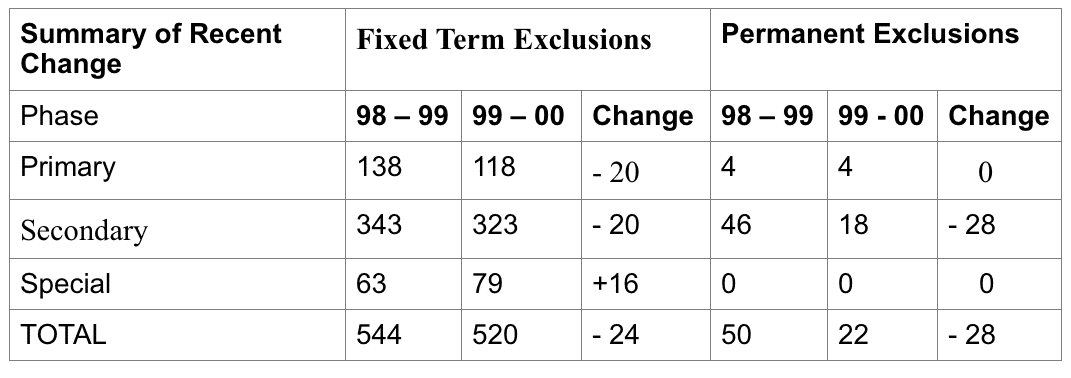

Table 1 Source: DfEE Form 7/ OFSTED LEA Profile (April 2000)

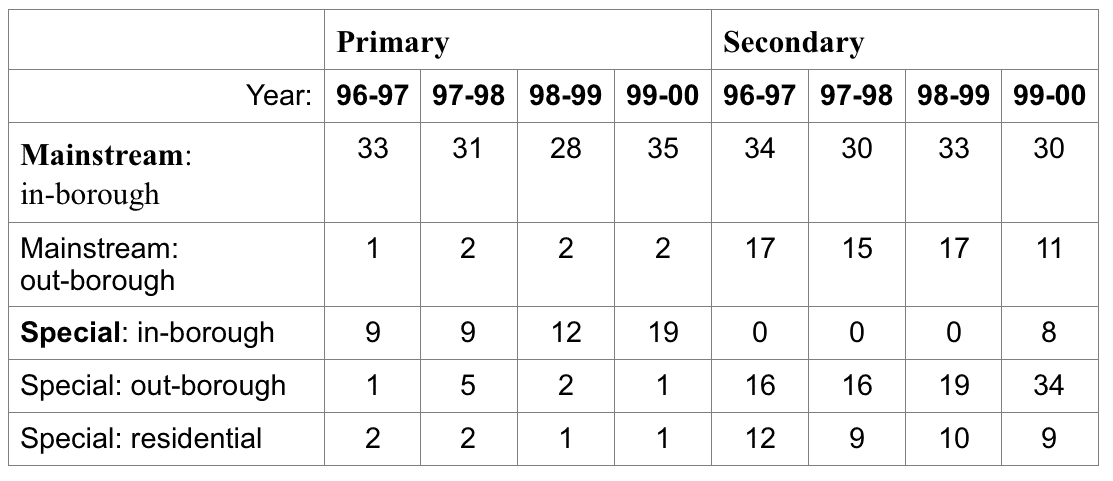

Table 2 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

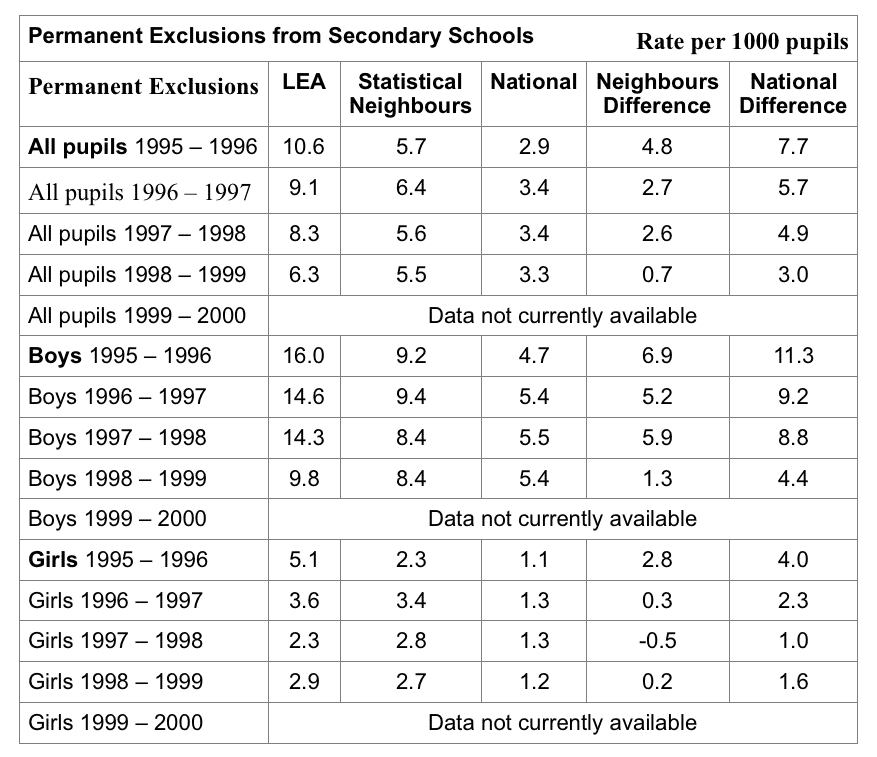

Table 3 Source: DfEE Form 7/ OFSTED LEA Profile (April 2000)

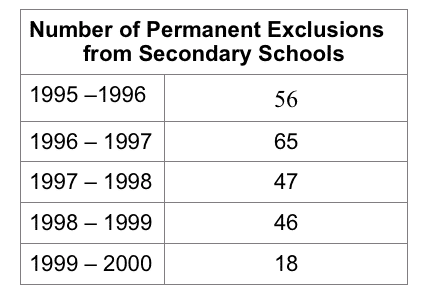

Table 4 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

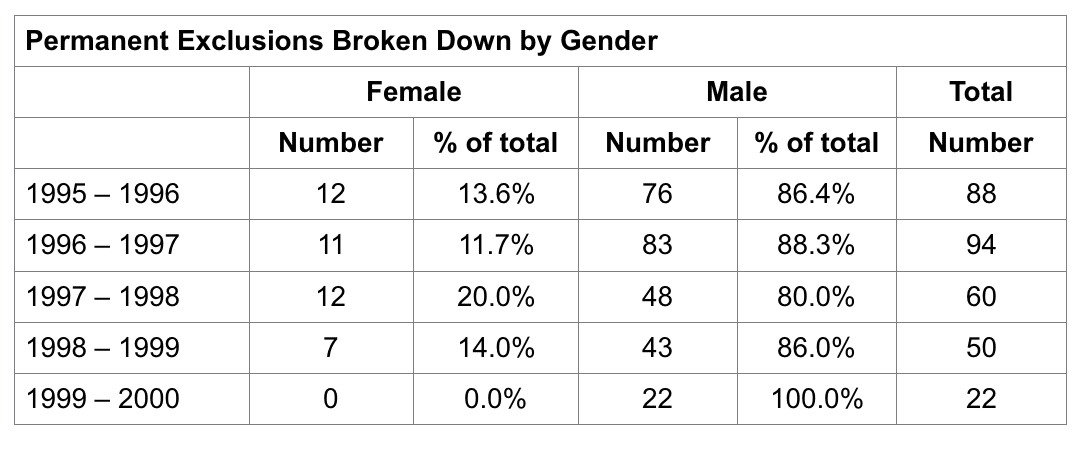

Table 5 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

Table 6 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

Table 7 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

Table 8 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

Table 9 Source: Hammersmith and Fulham Data

3.3.2 In both primary and secondary schools, the LEA’s exclusion rate over a 3 year period, despite decreasing, is well above the national average and also well above that of its statistical neighbours. Despite the targeting of resources there is still a high level of exclusions and although this is levelling off, it remains too high. Boys are consistently over-represented and this reflects national trends.

There is still a significant over-representation of pupils described using ‘black’ categories: approximately two thirds of both fixed term and permanent exclusions in 1999 – 2000 were of non-white pupils. This proportion is growing as the number of exclusions falls overall, and is a priority we are addressing though the Education Development Plan.

Statemented provision for pupils with emotional and behavioural needs.

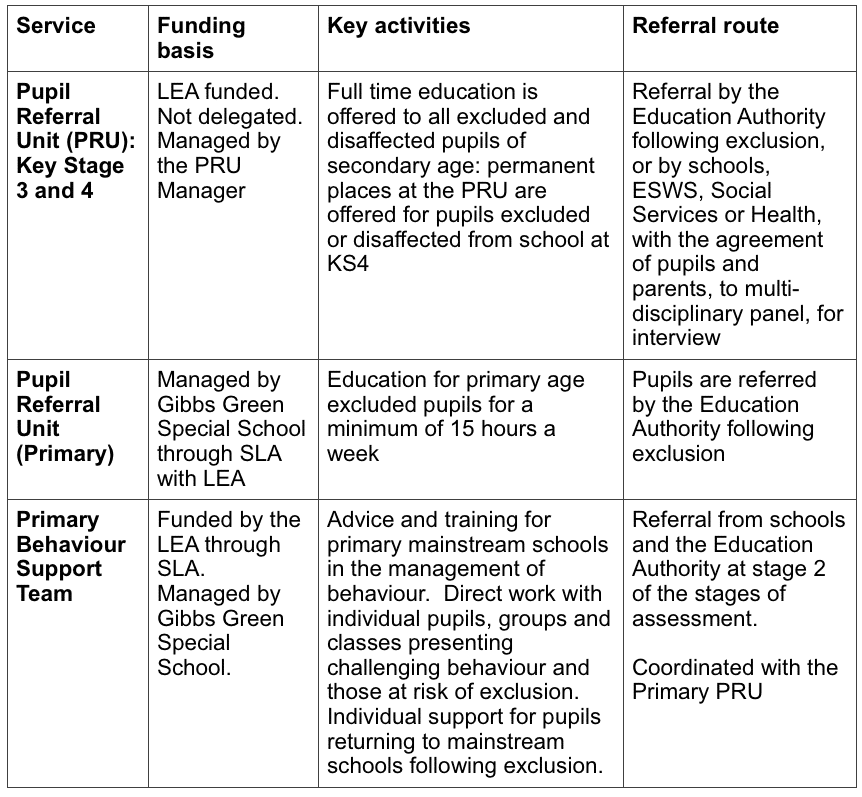

4.2 LEA Support Services

Complementing and interlinked with the above strategies, the LEA provides a range of services supporting individual pupils presenting emotional and behaviour difficulties, and their schools, a brief description of which is given on the following table:

5.2 Education for pupils excluded from school

5.2.1 The life chances of pupils who have been excluded from school can be reduced significantly by permanent exclusion. Experience in this LEA provides many examples of pupils who do make a success when moving to another school. However, if moving to another school is not possible or appropriate, pupils can go to the primary, Key Stage 3 or Key Stage 4 Pupil Referral Units (PRUs).

5.2.2. The alternative provision made for pupils at the PRUs is of a high standard: the LEA’s over-riding aim is to ensure that every pupil receives an education which is as near to mainstream as possible. When developing the curriculum for pupils with behaviour difficulties, the LEA also has due regard to the principles for inclusion as set out in the National Curriculum documents, and in particular, the points raised around:

- creating effective learning environments

- securing motivation and concentration

- providing equality of opportunity

- managing behaviour

- managing emotions

5.2.3 The PRUs additionally afford the pupils opportunities that they can miss while in a mainstream context, such as social skills training; personal target setting; team-building challenges; and sports activities. When pupils are older, the PRUs provide joint PRU/college courses, attendance at skills centres for vocational training and work experience.

5.2.4 The LEA offers full time education for all pupils who have been permanently excluded at the PRUs, although due to joint placements at college, work experience and pupil preference, hours of tuition typically range from about fifteen to twenty. There are twenty places at the Key Stage 3 (age eleven to fourteen) PRU and ninety at the Key Stage 4 (age fourteen to sixteen, but to eighteen in exceptional circumstances). Typically, the pupils in Key Stage 4 PRU remain there until statutory school leaving age, when they either leave education or transfer to further education (see below).

5.2.5 There are twenty full time places available for pupils who have been excluded at the Key Stage 4 PRU, and at times, when it seems appropriate, that number is exceeded. Further places are available for pupils who are disaffected with school. The criteria for placement at Key Stage 4 are that the pupil:

- has had continuing difficulties in the mainstream, resulting in disaffected behaviour

- demonstrates commitment to attend to continue education

- is able to manage the requirements of GCSE or other accreditation, within the context of the PRU, even if they may lack organisational and other relevant skills

- has demonstrated an ability to form adequate relationships within their peer groups and with adults, to facilitate their learning and development both educational and socially

5.2.6 All referrals to the PRUs must be fully supported by the parents, the pupil and the original school. The timetable and educational programmes at the PRUs are matched to the pupils’ individual needs. Pupils are expected to attend regularly, every school day, as set out in their timetable. The aim of the routine and educational programme is to provide for pupils an experience which is comparable to the experiences of their peers in mainstream schools and encouraging positive learning behaviour and habits. The curricula in the primary and secondary PRUs place a strong emphasis on learning through the National Curriculum so that pupils leave statutory education with their achievement recognised through accreditation. At Key Stage 4, a high priority is placed on ensuring pupils undertaking examination courses can complete their studies successfully.

5.2.7 Another key role for the Key Stage 4 PRU is preparing pupils for the transition from

compulsory education to further education and training or work. The Careers Service plays a significant role in this, working with pupils and their teachers. Hammersmith and West London College provides programmes, including vocational subjects, to pupils attending the PRU.

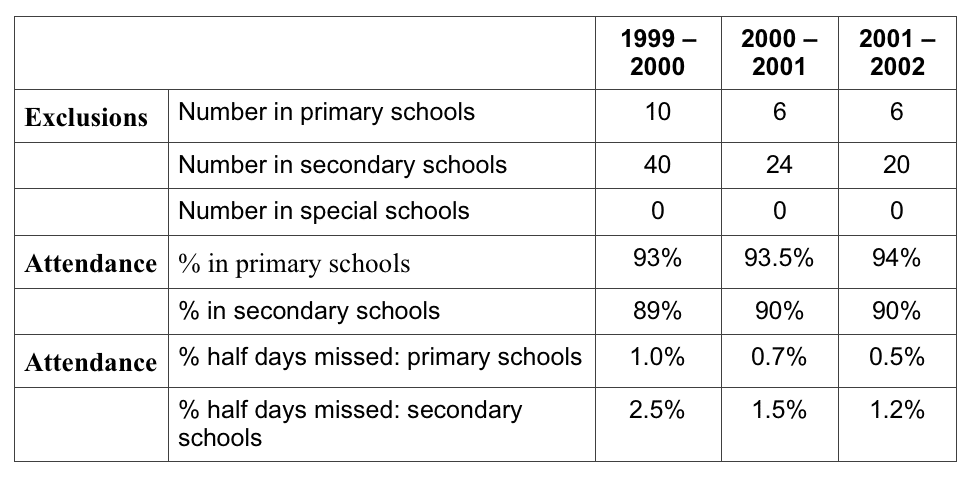

7.1.4 The LEA is proposing the following targets:

Table 16

These are ambitious targets which will represent a significant improvement on the current position and will bring the LEA close to national averages.