Using a Person-Centred Approach within Annual Reviews

Georgie Boorman, Cleo Timney, & Abigail Cohman – Trainee Educational Psychologists, University of Southampton

Shinel Chidley & Hannah Hall – Educational Psychologists, Hampshire and Isle of Wight Educational Psychology

“Can statutory meetings be person-centred?”

“What does the application of person-centred approaches look like in an annual review meeting?”

“Could professionals, families and young people benefit from this approach?”

These were some of the questions we found ourselves asking when embarking on our small-scale research project alongside Hampshire and Isle of Wight Educational Psychology service (HIEP). The requirement for genuine involvement of children and caregivers and growing interest in person-centred approaches across the county had led to its application in the context of annual review meetings. We were interested to explore the experiences of those facilitating these meetings to understand the impact of the use of person-centred practices in annual reviews.

PCPs are explicitly outlined within the SEN Code of Practice (DfE, 2015) as a requirement in the education, health and care plan (EHCP). Annual reviews are a part of this process, where targets, outcomes and provisions are reviewed at regular 12-monthly intervals. Yet, there is little statutory guidance regarding the specific requirements or format of annual reviews, beyond the principles of reviewing outcomes, and including the views of children and working in partnership with parents. As a result, annual review practices are suggested to vary across the country, and some young people still report feeling excluded from this process (Passy et al., 2017).

Person-centred planning (PCP) is an umbrella term for a range of person-centred approaches with aims of promoting service-user involvement, engagement and empowerment. PCP aims to allow the individual whom the meeting is about, and others in their networks and communities, to be more involved in planning, decision-making, and problem-solving. Benefits of using PCP approaches in meetings have been established in research within the UK and overseas. School meetings using a PCP approach have resulted in children and families feeling listened to and understood, increasing participation in meetings and ownership of actions from those involved, and establishing a fun and friendly atmosphere and greater enjoyment of meetings (Corrigan, 2014; Partington, 2016; White & Rae, 2016). The application of PCPs to annual review meetings has been a part of a broader PCP Project in Hampshire, which has involved a collaboration between HIEP and schools within the county. This has included the delivery of training to schools in the use of PCP in annual review meetings. The extension of the PCP project to annual reviews recognises the value of this model of working with young people and families and the potential impact it could have on statutory meetings.

Our small-scale research project aimed to explore the experiences of Hampshire-based educational psychologists and SENCos, who have facilitated PCP annual reviews, in order to understand the potential benefits of the approach in this context.

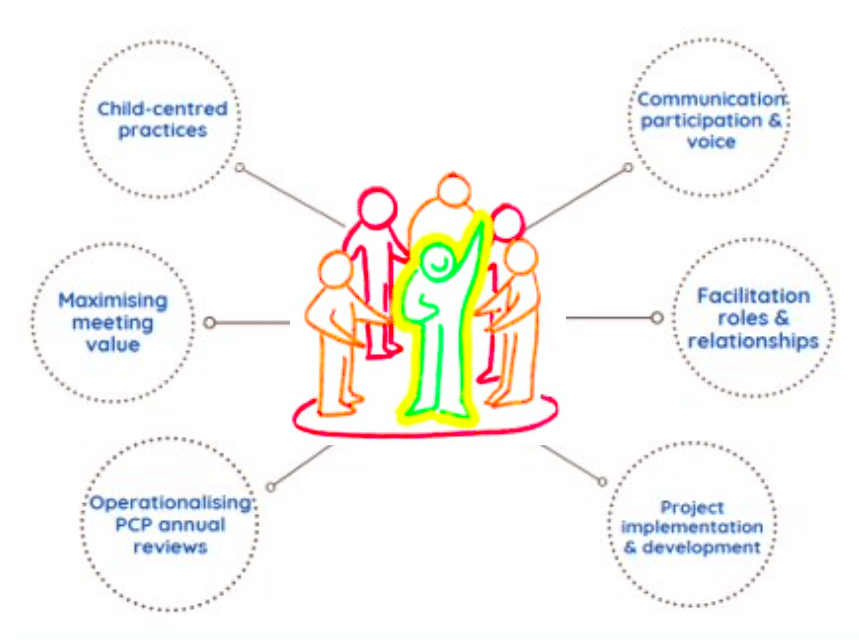

Findings from interviews resulted in the generation of six themes as areas of importance, including Child-centred practices; Communication, Participation & Voice; Facilitation, roles & relationships; Maximising meeting value; Operationalising PCP annual reviews; and Project implementation and development, as outlined below.

Information within these themes included the following:

Positive feelings associated with meetings: Professionals reported that they thought pupils enjoyed these meetings. They expressed that they thought children and families felt cared for and supported by school, enjoying being involved within the meeting and appreciating the focus on strengths.

Professionals believed that participants felt heard and supported: The PCP annual review represented more than just a meeting but was likened to an intervention. Professionals expressed that everyone within the meeting had a voice and opportunity to be heard. Relationships were strengthened through the meeting.

The meetings increased the feeling of shared ownership: PCP annual reviews could be less school/parent directed, instead focusing on things which were important to the student. An important outcome was the shared ownership of targets and outcomes, and increased responsibility held by meeting attendees.

PCP was a flexible tool for use in meetings: PCP approach represented a flexible way of working which focused on outcomes. Preparing people in advance supported effective and personalised meetings. Effective use of PCP annual reviews required some level of understanding and commitment from the school.

Participants also spoke about some of the practical implications of adopting PCP for annual reviews and some of the barriers that must be considered:

Preparation: It was important to manage expectations and understanding of the meeting format. Professionals expressed this allowed participants’ views, particularly children’s, to be shared more effectively in the meeting, as well as preparing adults that it would be a different type of meeting.

Facilitation: Partnership working between the facilitator and graphicer as part of the PCP supported effective communication throughout the meeting.

Graphics: The graphics/ visual representations undertaken during the meeting to record what was shared were important, developing and connecting points in the journey, reinforcing positive messages for pupils, and assuring everyone that their contributions were heard.

Reflection: Participants appreciated having time and space to share together, in some instances this required additional meetings and conversations between professionals and with families.

Target-focused: A focus on the future rather than the past was important. Encouraging participants to sign up to achievable actions within the meeting could help to increase motivation and ownership from everyone, rather than actions being the responsibility of one key person.

Listening and availability: The central focus within PCP annual reviews is the child or young person, rather than the paperwork, allowing for greater connection between attendees. This reduced meeting formality which was valued by participants and allowed people to feel they could contribute meaningfully, irrespective of their role.

Paperwork: The generation of information during the meetings and capture via the graphic was valued by practitioners. When annual review forms accommodated easy transference of information to formal documents, for example through the use of photographs embedded in annual review forms, this could save practitioners’ time.

Potential challenges: Participants recognised demands on school resources and staff time. Support is needed from senior staff members in order to invest time in the process and maintain a person-centred ethos in the school’s practice.

In summary, on returning to our initial questions “Can statutory meetings be person-centred?”; “What does the application of person-centred approaches look like in an annual review meeting?”; “Could professionals, families and young people benefit from this approach?” our small-scale research project demonstrated the potential value and possibility of using PCPs in statutory annual reviews. According to the professionals interviewed, PCP annual reviews provided flexibility and a personalised approach, which adapted to the needs of children and families, enabled attendees to feel heard, and empowered all meeting attendees. As a result, they were identified as a space for intervention, support and relationship building, rather than a bureaucratic process. It is also important to note some potential challenges to applying the approach, emphasising the importance of preparation and commitment to person-centred working from schools to promote the effectiveness of this model of working.

Hampshire SENCos who are interested in PCP approaches can contact their HIEP EP to find out more.

References

Corrigan, E. (2014). Person centred planning “in action”: Exploring the use of person centred planning in supporting young people’s transition and re-integration to mainstream education. British Journal of Special Education, 41(3), 268–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8578.12069

Department for Education and Department of Health. (2015). Special educational needs and disability code of practice: 0 to 25 years. Goverment Policies: Education and Health, January, 1–292

Passy, R., Georgeson, J., Schaefer, N., & Kaimi, I. (2017). Evaluation of the impact and effectiveness of the National Award for Special Educational Needs Coordination (Issue August). Plymouth University

Partington, L. M. (2016). Using Person Centred Planning with Children and Young People: What are the outcomes and how is it experienced at a time of transition from primary to secondary school? (Issue July). Newcastle University

White, J., & Rae, T. (2016). Person-centred reviews and transition: an exploration of the views of students and their parents/carers. Educational Psychology in Practice, 32(1), 38–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2015.1094652

For more on Person Centred Planning, our Online School has plenty of relevant courses. Or if you want something physical, our book Person Centred Planning Together is available for purchase